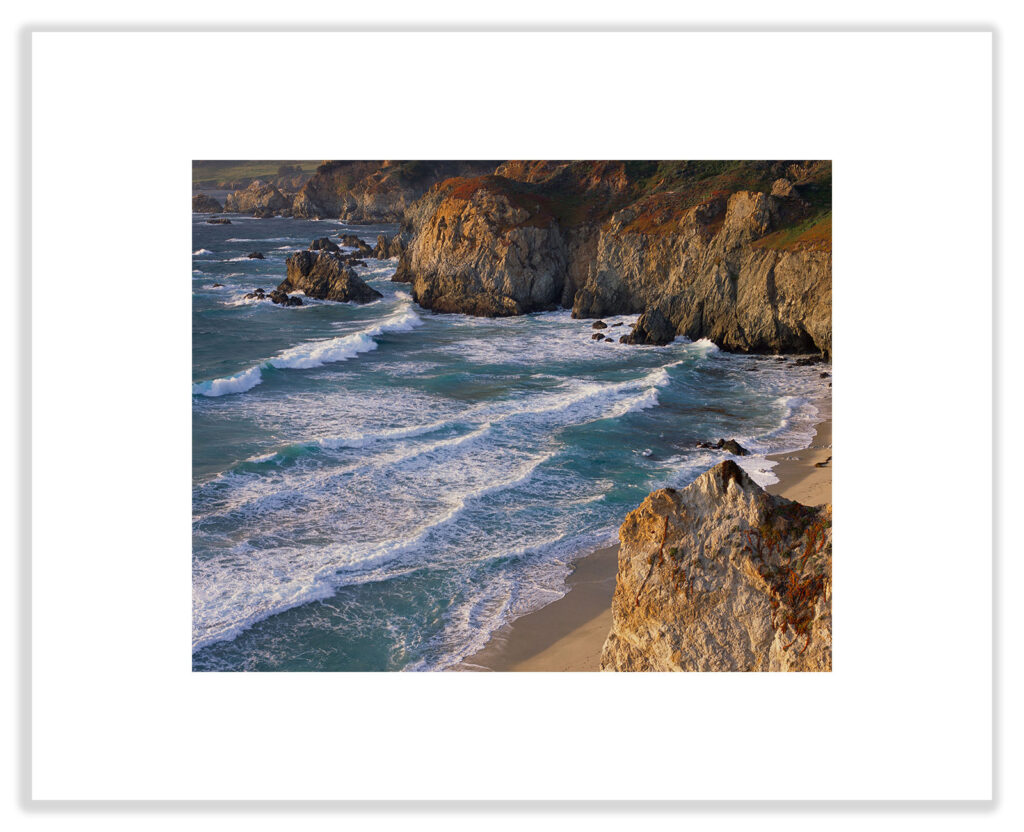

When you process your photos, are you trying to make them look good for screen or are you thinking about how they will print? And why is this even a question?

Well if you’ve ever made a print and had it come back looking nothing like your screen, you’ve experienced why this matters.

And not only do screens look different from prints, every screen looks different!

Every.Single.One.

If you don’t believe me, next time you walk into Costco, look at all the giant flat screen TVs and see how different every one looks.

The harsh reality is that when it comes to displaying our photos on a phone, tablet, or computer, It’s going to look different on every device. Throw in what instagram or facebook is doing to your photos and the same photo may even look different on the same device!

Trying to adjust to this every moving target is just chasing your tail. Great Rich, thanks for that little nugget of wisdom, but what do I do about it?

The answer lies in picking a more consistent standard, and for me that standard is prints.

With the right workflow, prints allow a higher degree of control and consistency. So instead of processing something to look good on my screen when I know it will look different on your screen, my goal is to process the file so that it will make a good print.

That’s a great goal, but what are some practical steps to achieve it.

Well, first, I have to know my monitor well enough to get past the screen to print differences I talked about earlier. I do that with a mix of experience, knowing what a certain result on screen will produce on print. I also use the info tool to read the pixel values ( “the numbers” ) so that I can make precise adjustments beyond what the screen can show me.

Learning to understand what how the screen will translate to print is what I call an “mental calibration” as you are training your vision to compensate for differences between the two. It’s a learnable skill, but it does take practice.

You can improve the process by “calibrating” your display with a device like the x-rite color monkey, and by using special reference monitors designed for screen to print matching ( I use a NEC MultiSync PA242W which you can read about in a previous article.)

Using that process, the processing decisions I make lead me to a file that I think will print the way I want. And if it will print the way I want, then this is the “most accurate” version of the file.

So when I share this file on the web or social media, I’m starting with the best possible source. Since I know it’s being viewed on countless devices I have no control over, I know that at least I was feeding in the best original I could.

So what happens if you work the opposite way? Making it look good for the screen with no regard for the print?

If you never print, that is a perfectly valid way to work. But it builds in a “gotcha” if you decide to print one of those files, chances are it will look nothing like your screen.

It’s really easy to push a file so far in such a way that still looks good on screen but moves outside the realm of what can ever be produced in a print. That doesn’t mean screens are better…in fact quite the opposite. What it means is that a screen is imprecise enough that it can hide a lot of bad processing decisions that become glaringly obvious on print.

There is a saying in the music world that if you can’t play well, then play loud. Screens are kinda like that.

You can get so used to hearing your photo “loud” on screen that when you switch to prints, which are capable of so much more depth and subtlety, that you can’t make the two meet. By processing my file for print, I don’t run into this problem.

Because I never expect the print to look just like it does on screen, I’m setting up a different expectation in my mind than that held by a photographer who seldom prints. Furthermore, I never expect that when I share my photo on the internet that it will look exactly the way it does on my precisely color managed monitor at home. It all comes down choosing a set of expectations that meet your particular needs, and using a workflow that helps you consistently achieve those expectations.