For me, looking at a finely crafted print is one of the most enjoyable experiences photography has to offer. But It’s wasn’t something I understood intuitively when I first started in photography, it’s an appreciation that developed from my experiences. And one experience in particular was a major turning point on that journey.

When I was just 20 years old, I took a workshop with John Sexton and Philip Hyde in Yosemite National Park, two superb photographers and masters of the craft.

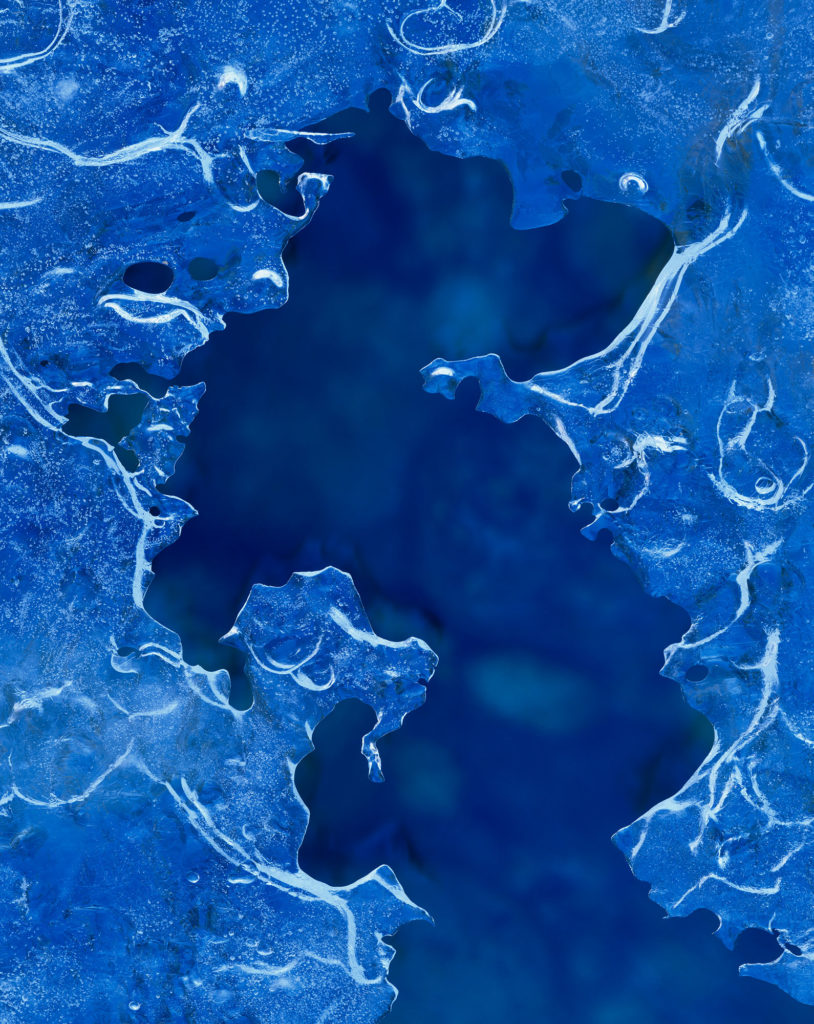

During the evening sessions, we looked at prints. Lots of them. And not just quantity, but quality. The prints Sexton and Hyde showed were mind blowing, transcendent, of which I have insufficient superlatives to express. Prints where you have to settle with that knowing look and head nod that can be shared by two people who have a similar refined knowledge and appreciation for fine printmaking of just how amazing they were because they are beyond words.

It was a life changing experiences, and that may be an understatement.

But why was this so profound? I’d seen their work in books before, but my real life exposure to truly fine printing was limited to what I’d seen at a couple museum exhibitions of vintage prints from other artists.

What was striking was how much more expression was revealed in the actual prints than could be shown by the reproductions made by ink on paper. Reproductions are never as good as the original, and that still hold true today.

Chances are the only way you’ve seen photographs from your friends and favorite photographers is on a screen, and maybe just your tiny phone.

I’d like you to consider that you’ve seen just a dull glimmer of what these photos are really like, because the screen is not capable of conveying all that a print can.Our screens and devices have allowed us to be exposed to more photography than ever before, but what we’ve gained in breadth, we’ve sacrificed for depth.

Just looking at a picture of a dish from a restaurant I want to visit isn’t the same as actually eating it. The picture is devoid of all the layers, flavors, smells, and complexities of the real thing.

And honestly, seeing a photo on a screen is lacking the same way to me. Now granted, my experiences have made me a bit biased. In my time as a curator at The Ansel Adams Gallery, I was exposed to the finest printing the 20th century had to offer. And as a fine art printmaker, I’ve been able to make museum quality prints for many photographers who’s work I greatly admire. I’ve seen a lot, and that my expectations are based on that.

But you don’t have to have the same experiences as me to appreciate this, and that is the whole point.

There is a much deeper layer of photography you can experience by looking at prints. There is a value in making your own prints, and taking the time to track down prints made by photographers who you’ve only admired in a instagram post. There is a whole world to discover beyond the screen, and all it requires is realizing this experience exists and taking the time to visit galleries, museums, and exhibitions to see real prints. If you don’t, then you are really missing out on one of the best parts of photography. So what are you waiting for.